The cost of further education is reshaping America. But as tuition prices soar across the country, one university in Kentucky has found a way to cover the costs. There's just one catch - the students have to work for it.

"Scholarships or student loans".

These were the available choices for 18-year-old Sophie Nwaorkoro to cover the costs of university.

A family crisis in her final year of high school derailed option one. She found herself homeless and without the financial support needed to help plug the gaps left from any scholarships.

Option two - taking out loans - would have placed Sophie among millions of her peers who enter adulthood bound to payments on their student loans. Most estimates put total student debt at $1.5tn (£1.2tn) - more than what Americans owe on credit cards. And nearly half of borrowers default on the loans.

HOLLY HONDERICH

HOLLY HONDERICH"I wouldn't have risked it," she says. "Debt kind of spelled out the end of my freedom."

Sophie had resigned herself to not continuing her education, until she got a call from Berea College, a small undergraduate university nestled in rural Kentucky.

The representative told Sophie they would cover everything.

"When she told me that I broke down and cried," Sophie recalls. "They just opened up a door that I was really sure had been closed."

Berea College was founded in 1855 by John Fee, a Christian minister and an abolitionist. It was the first integrated, co-educational college in the American South.

Its modern campus sits on the same ridge as the school's original building - now a small constellation of brick buildings and white columns that could be crossed, unhurried, in about 15 minutes.

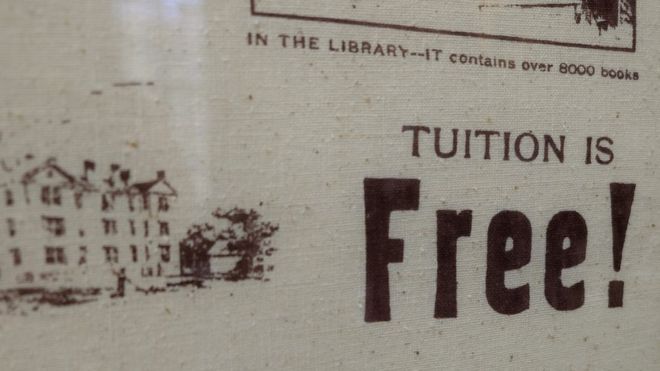

Since its inception, Berea was meant for students who could not afford college - costs were nominal, and students worked on campus to help support themselves.

BEREA COLLEGE

BEREA COLLEGEAnd, in 1892, it stopped charging tuition entirely.

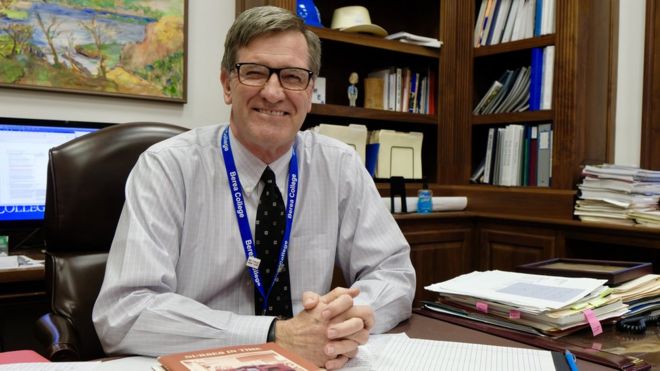

"What's unusual about Berea is that for, I'll bet 70% to 80% of our students, this is their only shot at a high-quality educational experience," says Berea President Lyle Roelofs.

More than half of Berea's incoming 2018 class had an expected family contribution of $0. The mean family income of a first-year student is less than $30,000 (£23,000). Around 70% of students are from Appalachia, where around one in five people live below the poverty line.

"We have always realised there are people who need education who can't afford to pay for it," says Mr Roelofs. "The 'how' is much more complicated."

The "how" is twofold.

First, there is Berea's endowment which, as of this year, has ballooned to $1.2bn (£930m), a product of nearly 165 years of growth.

"If you don't have tuition revenue, then you want to have a powerful friend like the American stock market," says Mr Roelofs.

The endowment is effectively safeguarded by the school's commitment to free tuition. A renovation or campus upgrade will only be approved once every student's tuition is assured. Its growth has also been spurred by a particularly prescient vote by Berea's board in 1920, which ensured that any unrestricted bequests - donations left without a specific purpose - would be added to the endowment.

Now, about $60m is withdrawn from the endowment each year to support Berea's operating budget, including tuition.

HOLLY HONDERICH

HOLLY HONDERICHThe second unique feature at Berea is the labour programme, which requires each student to work on campus for at least 10 hours every week, similar to a federal work-study programme at other US universities.

"At Berea College, no student pays tuition for a high-quality education, but every student works," says Roelofs. "We don't just admit every student, we hire every student."

The jobs are essential to Berea's operation - both the students' labour and a portion of their pay cheque is used to keep the college running.

"It's not the most romantic thing," says Sophie who, in her role in the dining hall, works with "absolutely everybody's trash".

"I know some people might look down on it, but you kind of go in there with a sense that 'I'm doing something that's helping people.'"

And there's an obvious payoff - in 2019, 49% of Berea students graduated with zero debt, even after food, housing and other living expenses. For those that did, they held an average of $6,693 - around one quarter of the national average.

Berea is small, about 1,600 undergraduate students and - for obvious reasons - it doesn't boast many shiny amenities that could be used to sell itself at college fairs.

"We don't add those kinds of appealing features that are just there to attract wealthy students to come," Roelofs says. "You know, a lazy river or a climbing wall contributes almost nothing to the educational experience".

It lacks the name recognition of elite schools scattered throughout the country's coasts, and is only reliably known to those living in surrounding Appalachia.

HOLLY HONDERICH

HOLLY HONDERICH"When I heard about it, it sounded sketchy," Sophie said. "If it were free, then it must be poor quality."

But Berea does not look or feel like a discount university.

The campus is archetypically collegiate. Student life is narrated by church bells, the grounds punctuated by tree-lined quads. It is ensconced within 9,000 acres of the college's own green space, which drifts into hundreds of miles of forest in the Appalachian foothills of eastern Kentucky.

At the school in October, students often made casual reference to their "Berea story", campus shorthand for the challenge or trauma that threatened their chance at college - a common trait among students.

But just as quickly, the conversation turned back to plans for homecoming or upcoming exams. This is perhaps Berea's greatest feat - for its students, daily life is insulated from pending student debt.

HOLLY HONDERICH

HOLLY HONDERICHIt is also the most selective school in the state, according to Berea's admission records. Students are accepted on the grounds of both academic performance and financial status.

In 2018, 97% of its incoming class were eligible for Pell grants, a federal grant awarded only to those "who display exceptional financial need".

Many of the students mention Berea's academic rigour, a surprise for some who assumed that "tuition-free" is code for cheapened education.

"You definitely can't come here and slack off," says Sophie.

"I think we're so used to colleges being so expensive that we kind of expect them to be expensive. We dismissed the idea of a college that can be affordable."

The struggle to pay for college is a defining feature of working families in America, says New York University Professor Caitlin Zaloom, who studies the toll of student debt on families. "The escalation in college costs can't go much farther."

The stress carries on long after graduation both for parents and for students, she says. "The debt and the costs orient their lives for years afterwards."

But as going to university increasingly becomes a "moral imperative", a requisite for job stability and upward mobility, government funding for higher education has plummeted.

HOLLY HONDERICH

HOLLY HONDERICHBetween 2008 and 2017, overall state funding for public two- and four-year colleges fell by nearly $9bn after inflation, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a non-partisan research group.

These cuts to government funding have been met with steep tuition hikes, effectively pushing American families toward loans.

"The largest lender is the federal government," says Ms Zaloom. "It is very clear that the federal government is expecting its citizens to pay for college with loans. That's the message that families get very, very clearly from day one."

In just the past decade, student debt has more than doubled, jumping from $675bn to today's $1.5tn.

"I think we're really at a breaking point," says Ms Zaloom. "It's simply not morally supportable to require young adults to start their lives in so much debt."

So what should be done about it?

There is broad agreement that university tuition in the US is too expensive, but there is no resulting consensus on the solution. Most American colleges provide a patchwork of scholarships and loans to help lighten the cost.

HOLLY HONDERICH

HOLLY HONDERICHThe notion of doing it for all - like Berea - is slowly gaining ground.

New Mexico's state government recently announced plans to make state schools free for all students, regardless of family income, using revenues from the state's booming oil industry. And some leading candidates in the 2020 Democratic race have embraced the concept of free tuition.

But Mr Roelofs thinks "free tuition" can be a fragile tagline when left on its own.

Just declaring college education free is not the answer - it needs to be free and high quality, he says.

For its 1,600 students, Berea's model works. But it has had a 126-year head start.

"In order to really do what Berea does, you have to come up with a pretty big amount of money just to get yourself going," he says. The challenge is then "scaling up".

HOLLY HONDERICH

HOLLY HONDERICHBerea's small size and its long-term commitment to growing its endowment for free tuition have given it a sizable lead that other universities may struggle to reproduce.

But Mr Roelofs believes Berea's model can be influential - if state governments provide more funds to the public universities, where 80% of US students attend.

"I do think there could be a Berea in every state," Roelofs says. "There's only one and it's in Kentucky, but in every state there are kids who, you look at them, and you say, 'boy, they deserve a better chance than they're getting'."

For Sophie, that chance was "one in a million".

"If this opportunity were taken away from me, I don't know where I would end up, I don't know what gutter I'd be sitting in," she says. "This school means the world to me."

Now, as a first year student at the school she calls her "unicorn", Sophie is studying physics, singing in a choir and performing beat poetry in a school pageant hosted by the Black Student Union.

After, she hopes to become a doctor - obstetrics and gynaecology - meaning four years of medical school, she says.

"Which, hopefully I'll be able to afford."